Fashion or style is unquestionably central to all subcultures, as each subculture is organised around or based upon certain features of costume, appearance, and adornment that render them distinctive enough to be recognized or defined as a subset of the wider culture. The official birth of 'punk' as a subculture went hand in hand with the the birth of ‘punk fashion’, which has been credited to entrepreneur Malcolm McLaren and fashion designer Vivienne Westwood.

Being uninspired by the hippie

movement of the late 1960s, the pair became interested in rebellion and in

particular 1950s clothing, music and memorabilia. Vivienne began making

Teddy Boy clothes for McLaren and in 1971 they opened their first boutique Let

it Rock at 430 Kings Road.

By 1972 the designer’s interests had turned to

biker clothing, zips and leather, and the shop was re-branded with a skull and

crossbones and renamed Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die. Westwood and

McLaren began to design t-shirts with provocative messages leading to their

prosecution under the obscenity laws; their reaction was to re-brand the shop

once again and produce even more hard core images. By 1974 the shop had been

renamed Sex, a shop "unlike anything else going on in England at the

time" with the slogan "rubberwear for the office".

By 1976, The Sex Pistols' 'God Save the Queen' went to number one and was refused airtime by the BBC. During this time the shop

reopened as Seditionaires, transforming the straps and zips of obscure sexual fetishism into fashion and

inspiring a do-it-yourself (DIY) aesthetic. The media called it ‘punk rock’ and the label stuck. The UK mainstream punk fashion thus became theatrical and stylized with studs, safety pins,

purposely ripped t-shirts, bondage gear and outrageous makeup. Most importantly, all of this activity took

place outside of a ‘performance art’ context: this was happening on the street.

Writer Dick

Hebdige states that…"Punk was driven to assert that the punks' 'cut-up' wardrobe of bondage trousers, school ties, safety pins, bin

liners, and spiky hair signified meaningfully only in terms of its very

meaninglessness, as a visual illustration of chaos."

Melbourne Punk Fashion:

Strongly Influenced by both UK and USA punk music, by 1977 the Melbourne punk scene had emerged, and the accompanying fashion aesthetic quickly evolved into a very individual and home-made look, more comparable to the Hollywood style of punk. Discarded glamorous evening clothes were found in op-shops, re-worked and worn as everyday clothes. Underwear was worn as outerwear. Stockings and fishnets were deliberately torn. Negligees were worn as day wear and loose, sheer semi-translucent fabrics were trimmed with lace or other fine material and bows. Jackets and t-shirts were also hand painted with words and slogans and decorated with badges. Often, hair was cropped and deliberately made to look messy, in reaction to the typical long smooth hair of the 1960s and early 70s. It was also often dyed with brilliant unnatural colors.

As Lisa Dethridge puts it in The Ballroom book by Dolores San Miguel:

"The costumes are exquisite... Everyone is decked out in tribal insignia; scarves, neckerchiefs, lace, tassels, gloves, boots, specs, sunglasses - anything to add character, status and fascination. Costumes and stockings are strategically ripped and paint-spattered. Jewellery is big and metallic; studs, rings, chains and safety pins in noses, ears and costumes."

But punk fashion was not just limited to the streets or smoky venues. Also Inspired by the punk movement of London, several Melbourne fashion designers started experimenting with avant-garde and innovative designs of their own.

One such notable designer is Jenny Bannister who successfully merged the anarchic, anti-elitist, do-it-yourself attitude of punk with fetish aesthetics. In Bannister's work traditional materials, construction methods and fashion trends were abandoned or reworked and were instead replaced by unusual materials - leather was cut, perforated and studded together in an ad-hoc yet sophisticated way, and denim was printed to resemble cracked mud. Using plastics, chain and all manner of things to create her thematic ranges of club wear and even bridal wear, Bannister became known for recycling materials and creating an element of shock to a look that was decidedly "chic savage".

"I’d go to see Nick Cave, The Boys Next Door, The Church, The Models and The Saints at the Crystal Ball Room in St Kilda or the Tiger Room in Richmond. I spent my life between these two venues. I guess we were all just basically into punk in the late 70s." (Jenny Bannister)

Artists, designers, craftspeople and fashion designers were soon exploring dress as a creative outlet, resulting in a blurring of the boundaries between art, craft and fashion. It encouraged designers to take a more independent approach to fashion design and to consider limited production ranges as a viable part of the Australian fashion industry. It also gave rise to a number of boutiques in Sydney and Melbourne specialising in independent art clothes designers. e.g No Future, Last Daze, Trash, Flamingo Park, Clarence Chai and ultra-hip The House of Merivale whose insight and new wave cutting edge designs were to define Melbourne's unique glam-punk culture.

This "radical fashion movement" also encapsulated a clutch of other notable Australian designers such as the late Peter Tully, Katie Pye and Kate Durham for example, all whom experimented with unlikely materials and found objects. Other successful fashion designers such as Alannah Hill, Martin Grant, Fiona Scanlan and the Liano sisters also emerged out of the punk/new wave eras.

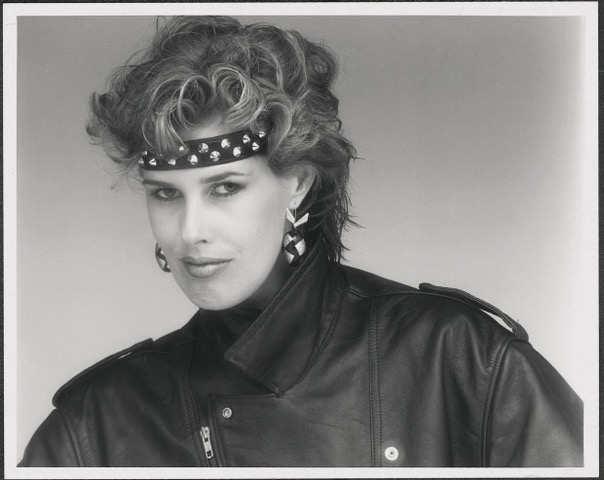

Another vibrant and beautiful woman of the late '70s and early 80's punk scene was Deborah Thomas, who would eventually go onto become the Editor for Cleo Magazine, Elle Magazine and the Australian Women's Weekly.

Dolore San Miguel writes about Deborah in her book The Ballroom: the Melbourne punk and post-punk scene:

"I met Deborah Thomas at various gigs as she dated Bohdan (JAB) for a time. Both of them were very tall and extremely stunning. When they entered a room together, it was like a magical vision from an Italian or French Vogue advertisement. They both had impeccable fashion taste and their entrance, anywhere, would cause jaws to drop and chatter to hush."

Deborah has her own memories of the early punk scene in Melbourne:

"I loved the raw energy of the loud and discordant music. The punk anthems from the Sex Pistols, The Saints and later, Blondie and the Clash. I will never forget seeing The Boys Next Door at one of their early concerts with a young Nick Cave out front singing a punk cover of Nancy Sinatra’s, 'These Boots Are Made for Walking'. Behind him was Vulva, a female backup singer throwing raw mincemeat into the audience. I thought wow, I have arrived. I love this!

It was circa 1977 and I was at art school at the time and Nick was a fellow student in the year below. We were studying painting at Caulfield institute of Technology and there were a number of students in bands including Nick Seymour (later to be one of Crowded House, whilst his brother, Mark, led Hunters and Collectors). We were all looking for something new, something different, rebellious, loud and exciting. Something that embraced every aspect of creativity from music to fashion, to art, graphic design, film, poetry and writing.

I refer to it as Melbourne’s Renaissance period with venues such as the Tiger Lounge in Richmond and the Crystal Ballroom at the George in St Kilda. A couple of times a week we would dress up and venture out to see fabulous punk bands, including the Models and JAB, with a fire-eating, leather-clad, Bodhan X as the lead singer. It was love at first sight …and electrifying sound.

We dressed in Jenny Bannister originals, Vivienne Westwood if we could find them, or clashing vintage pieces from the local op-shops put together with a fashionable Fuck You to mainstream fashion. Lashings of black eyeliner, teased, bleached blonde hair, ripped clothing and safety pins. It was about individual expression but also, being a nice Melbourne girl, always done with lashings of grace and style. Or at least I thought so. That's what made us so different form the UK punks, we were from nice middle-class homes, not rebelling against a repressive society with a down-trodden underclass, but rather redefining ourselves as spirited, modern, alternative creatives.

It was without doubt one of the most exhilarating periods of my life and many friendships from that era continue to this day. As does my love of punk and cult fashion." (Deborah Thomas)

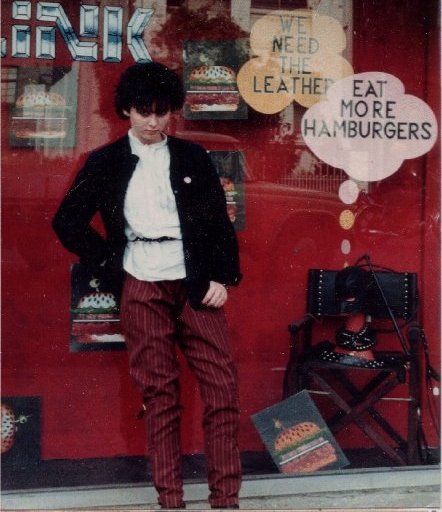

Although by 1980 the punk influence had lost its momentum in the UK, the young punks of Melbourne had no thoughts of conforming to a more formal style. Instead, they continued to experiment with the punk look and DIY ethos by opening up their own boutiques and selling their own designs.

One prime example of this was Eccentric Clothing in

"We had a shop at the time called Eccentric Clothing opposite the Tote Hotel on Johnston st. We would make these ridiculous clothes and try and sell them during the day, while practicing there with the band as well, then do gigs at night at the Tote." (Kate Buck)

As 'punk' became 'new wave', elements of the highly stylized and androgynous 'new romantic' look crept into the Melbourne post-punk scene, and suddenly ruffles, velvet and eyeliner were a popular option - especially for males. While other inner-city boutiques such as Blues Point, Blonde Venus, and Nostalgia also sold punk clothing, hair salons such as Ben Taylor (later to be called Godfrey & Taylor) was where many punks went to get their hair dyed, coiffed and spiked to perfection.

Established in 1977 by Ben Taylor and Gail Hedley, by 1980 the salon was boasting clients like Eric Gradman (Man & Machine), Nick Cave (Boys Next Door), Paul Elliott (Polyester Records) and the cast of the now iconic film Mad Max 1. The salon not only sold punk t-shirts designed by the late fashion illustrator Robert Pearce (Fashion Design Council) but was also the first salon in Melbourne to stock hair gel. By 1981 other hair salons such as RIFMIC, Nouveau, Sweeney's and Inspiration and Waves were also giving hairstyles like quiffs and bouffants to the ever-growing staple of flamboyant youngsters immersing themselves in this exciting subculture.

"It was really the beginning of people being aware of products and gel wasn't readily available, but we found one company that had gel which we sold quite a bit of. Before that people were using sugar and water, wallpaper paste, soap, bryl cream – anything that made their hair stand up. Hair was a big part of the punk look; people were trying to shock!" (Ben Taylor)

The Chaos of Fashion:

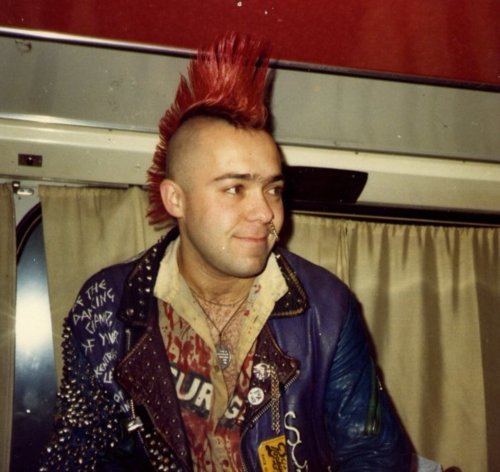

By the end of 1981 several post-punk bands were still featuring prominently in the Melbourne underground music scene, but the sound of punk was about to change dramatically; and as the music became faster, louder and more aggressive, so too did the fashion. Strongly influenced by a combination of USA and UK hardcore punk bands, the next generation of Melbourne punks were ready to take over from their predecessors, and they had their own shock look to prove it.

While the 'Anarcho-punks' opted more for an all-black militaristic clothing style, other Melbourne punks resonated more with the USA Hardcore scene and opted for a more dressed-down style - t-shirts, jeans, hooded sweatshirts, army pants, combat boots or sneakers and crewcut-style haircuts. However, the majority of Melbourne punks resonated with the more provocative fashion styles of punk and, influenced by UK hardcore punk bands like The Exploited, GBH and Discharge, punk kids were about to become every mother's worst nightmare.

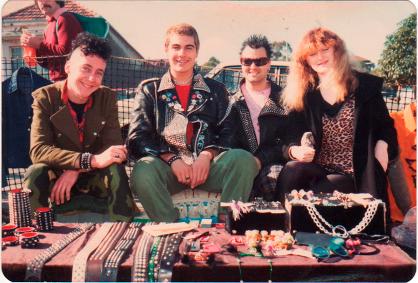

Brightly-coloured hair, elaborate Mohawks and liberty spikes, bold makeup, torn clothes, band patches, safety pins, studded leather jackets and wristbands, bondage pants, and Doctor Marten boots were to become the main uniform of the Melbourne hardcore punk, and while op-shops were still a major source of affordable clothing, now a 60's dress could look good with a Mohawk, bold makeup and army boots. As with the punks of the 1970s, DIY fashion also played an important role in the 1980s punk scene, and a major pastime for many punks was spending hours hand studding jackets, belts and wristbands, and screen printing their own t-shirts with political slogans and band names.

"Hardcore House was a commune... we did a lot of combined things here like screen printing and tattooing and we rehearsed here almost every day of the week as well as seeing a really huge art movement taking place." (Smeer)

And for those punks whose DIY skills were lacking, inner city boutiques like The Wrong Shop and labels like 3rd Cockroach, Roger Ramjet and Young Smirlis sold punk inspired clothing, while flea markets, like the Camberwell Market, were also popular for treasure hunting.

"A bunch of us were sitting at a table at the Ballroom and I was wearing my favourite outfit which consisted of a black mohair jumper (knitted by my grandmother!), white shirt with small collar, studded wrist bands and belt (bought from 'The Locker Room', “Adult” shop), black pointy-toed boots with buckles and a gentrified pair of bondage pants. I had spotted these in some up-market boutique in South Yarra, and had put them on lay-by for ages as they cost a small fortune...they were still an article of clothing you couldn’t buy anywhere in Australia. Of course there was always mail order to the UK, but that often came with a 3 month wait. " (Cherry Ripe)

Leigh Bowery:

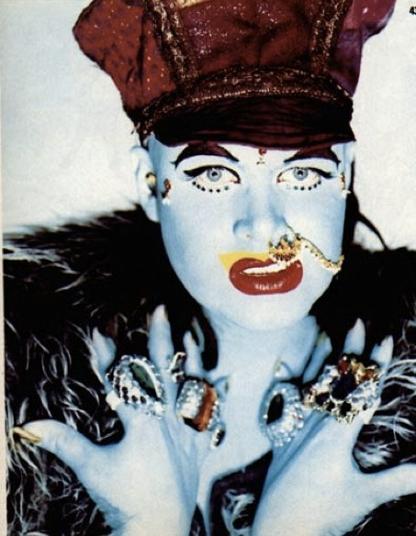

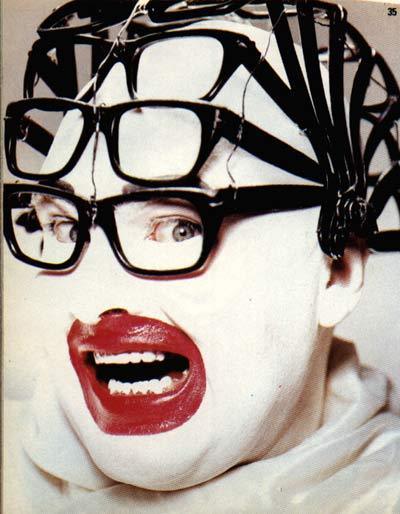

One cannot mention DIY punk fashion without mentioning fashion icon, performance artist, club promoter, actor, pop star and model Leigh Bowery. Bowery was born in 1961 and raised in Sunshine, a baby-boomer, semi-industrial suburban sprawl, west of Melbourne. He attended Sunshine Primary School and later, Melbourne High School, and from an early age, he studied music, and played piano. He passionately wanted to be a fashion designer and studied for two years at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) before becoming disillusioned by the restrictions imposed by formal training. Fueled by the visual culture of style magazines, Bowery was attracted to London and its 'New Romantic/Blitz' movement; where fashion, art and music were fused under the glamorous spotlight of the nightclub scene.

Moving to London in 1980, Bowery soon became an influential and lively figure in the underground clubs of London and New York, as well as in art and fashion circles. He attracted attention by wearing wildly outlandish and creative outfits, including makeup, wigs and headgear that he made himself, all of which combined to be striking, inventive and often kitschy or beautiful. Bowery became friends and roommates with Guy Barnes (known as ‘Trojan’) and David Walls: Bowery created costumes for them to wear, and the trio became known in the clubs as the ‘Three Kings’.

As Robyn Healy writes in her publication titled Taboo or Not Taboo, the fashions of Leigh Bowery:

Leigh Bowery was..."An extra extrovert, the ultimate spectacle, the fashionable performer, the grand poseur, Bowery communicated through his blatant sexuality, his extreme physical exaggerations, and his outrageous dress codes. Bowery was not simply dressing up; it was his lifestyle and commentary on the mundane, a joke about appearance. His collections or ‘looks’ were based on himself manipulating his body with clothing and make-up. Working outside the comfort zone, he developed a clothing aesthetic that few would dare follow. Original, provocative, evolutionary; Bowery manipulated clothing to totally change one’s appearance, like a form of cosmetic surgery.” (Robyn Healy)

Bowery was also strongly influenced by the iconic punk fashion designer Vivienne Westwood:

“Bowery’s costume designs were

complex, technically difficult and fantastic. By 1985 they bore no

similarity to the catwalk or street styles of London or the rest of the world.

Vivienne Westwood initially was a great inspiration to Bowery,

particularly her anti-establishment spirit, her distortion of clothing and

body forms, and her design mantra that clothing could be subversive.” (Robyn

Healy)

In 1985 Bowery became the public face of the nightclub Taboo, which was originally staged only once a fortnight as an underground party, and then opened as a club. Wearing a different outfit every week, Bowery was a club promoter as well as being the main attraction. The club was known for defying sexual convention, for its wild atmosphere, and for its sometimes-unexpected song selections. It was also clubs that provided the major market and audience for generating clothing that was beyond one’s wildest dreams/nightmares.

"Without the assistance

of the slick, branded imagery associated with major fashion labels and huge

marketing budgets, Bowery’s fame and reputation rested solely on being seen.

His creations were documented and celebrated in the London style magazines, i-D, The

Face and Blitz; his antics were reviewed in the club pages,

communicating his visual language. Promoting the fringe, these magazines

gave copy and editorial to the young and original, promoting an ideas

culture that supported independent design.” (Robyn Healy)

And although Australia was often months behind the London fashion world, the fact that Bowery was a Melbourne boy was not lost on Melbourne fashion lovers of the day.

“In Melbourne the enclave of independent fashion designers and boutiques situated in Greville and Chapel streets would proudly display the latest edition of The Face or i-D in the shop window, and they were indispensable reading in every hairdressing salon. Many Australians followed Bowery’s career and lifestyle through this source, even the interior of his flat that he shared with Trojan was featured – walls covered in Star Trek wallpaper, clumps of plastic flowers decorating the skirting, and UV-lit. Interviewer: Does the interior of your home match the interior of your mind? Leigh and Trojan: Yes, it’s an extension of what we wear." (Robyn Healy)

Leigh Bowery died in 1994, from an AIDS-related illness. However, his influence has reached through the fashion, club and art worlds to impact, amongst others, Meadham Kirchhoff, Alexander McQueen, Lucian Freud, Vivienne Westwood, Boy George, Antony and the Johnsons, John Galliano, the Scissor Sisters, David LaChapelle, Lady Bunny plus numerous Nu-Rave bands and nightclubs in London and New York City which arguably perpetuated his avant-garde ideas.

An exhibition of Leigh Bowery’s work was staged in Australia in 1999: Leigh Bowery: Look at Me at the RMIT Gallery, Melbourne, curated by Robert Buckingham and designed by Randal Marsh, included original costumes, videos and photographs.

Party Architecture:

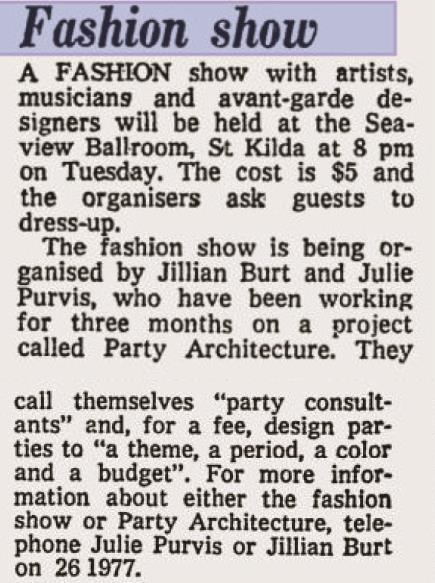

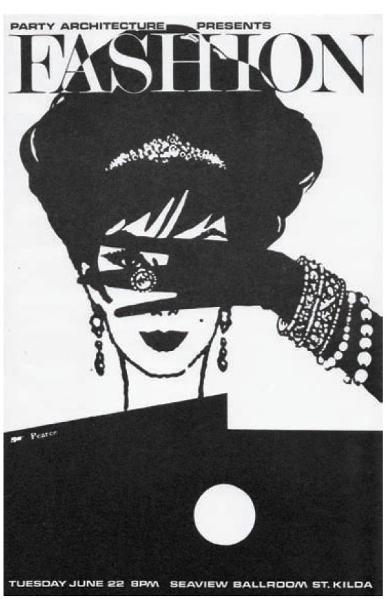

Emerging out of the post-punk/hardcore crossover were 'party consultants' Julie Purvis and Jillian Burt who put on the first Party Architecture fashion show at the Crystal Ballroom in 1982. Working in conjunction with 'set designers' Kate Durham and Robert Pearce, the parades consisted of around twenty Melbourne fashion designers and artists who were approaching fashion with an adventurous and independent spirit.

Each parade innovatively incorporated live music, hairdo demonstrations and stand up comedy and film, with original music written for each designer by Dean Richards (Equal Local). After the huge success of Fashion '82, a subsequent and final parade was held in 1983 and included designer and artists such as Jenny Bannister, Clarence Chai, Sara Thorn & Bruce Slorach, Beverly Boyd, Matthew Flinn, Maureen Fitzgerald, Desbina Collins, Rosslynd Piggott, Kirsty James, Inars Lacis, Raro, Vanessa Oliver, and Jane Stevenson.

"Party Architecture deliberately hedges defining the term 'fashion'... Who is brave enough to draw the line which determines where what is fashionable ends and where fashion becomes art? Rather than trying to wrestle a workable definition of fashion to the drawing board, we have selected a number of people who express an individuality, a perfect conviction for their creative spark that is sometimes OR all the time founded in the designing and constructing of apparel." (Julie Purvis & Jillian Burt - Fashion 83 program)

Showing their collection for the first time in Fashion '83 were now iconic fashion designers Sara Thorn and Bruce Slorach. Experimenting with textiles, including the use of hand silkscreen fabrics and later jacquard woven with their eclectic mix of imagery, the pair capitalized on their art school background by transforming relatively cheap material (cotton jersey, calico) into bespoke fabric.

Influenced

by Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Buffalo Gals’ video clip and Vivienne

Westwood’s ‘Buffalo’ collection (1982) the pair had immediate success with their 'Cowprint' dress which was modeled by Alannah Hill in Fashion '83. Receiving much media coverage and interest from international boutiques, Sara and Bruce launched their own label ABYSS Studio in 1983, stocking fashion, textiles and accessories.

By 1986 Bruce and Sara opened an adventurous retail outlet called Galaxy Emporium, the same year they introduced jacquard woven textiles into their collections. Galaxy became the place that provided the cool outfits for the urban post-punk, fashion savvy crowd, and for the denizens of the emerging club scene, although mainstream fashion press sometimes got it wrong and presented them as beach wear.

"Bruce and I would spend all day printing fabric, cutting it up into t-shirts and mixing and matching prints to create this original look. The concept was to bridge art and fashion and it very much came out of the DIY punk ethos...you didn't have to be trained, you could find your own creative voice." (Sara Thorn)

Click HERE to view the full 1983 Party Architecture program

|

Making it up as we went - Party Architecture - Merryn Gates.pdf Size : 636.869 Kb Type : pdf |

|

Into the Abyss - Merryn Gates.pdf Size : 453.184 Kb Type : pdf |

The Fashion Design Council:

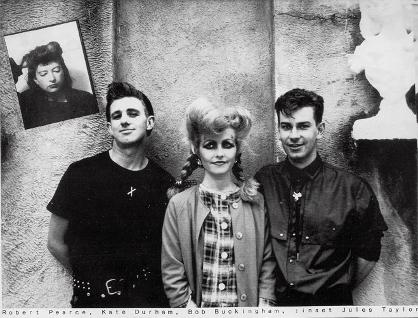

Hinged on the success of Party Architecture, and with a $4000 grant from the Victorian Ministry of the Arts, the Fashion Design Council of Australia (FDC) was established in 1983 by jewellery designer and artist Kate Durham, Arts/Law graduate Robert Buckingham and fashion illustrator Robert Pearce. With the aim of promoting and supporting emerging independent Australian designers, the FDC advocated sustainability of independent design and promoted the virtues of ‘high risk dressing’ (a phrase that came into use in the middle of 1983).

Its manifesto stated a passionate commitment "...to the development of the art of fashion design, to the individualistic, the idiosyncratic, the experimental, the new and provocative, both in its wearable and unwearable form...separate to the conventions of mainstream and commercial fashion, the European tradition, the stranglehold of fashion houses." This declaration offered young designers an incitement to break free from mainstream fashion industry practices of ‘bland middle ground’ and collectively support each other in this new affiliation of a cooperative collective and progressive enterprise.

"They (Party Architecture) said "do something with this". In fact we understood very little of what they were talking about, but we did have a fierce belief in the validity and strength of younger Australian fashion..." (The Politics of Fashion - FDC)

Dedicated to encouraging pride, independence, self-employment and entrepreneurial skills to emerging non-mainstream Australian fashion designers, the FDC was officially launched at the Hardware Club in February 1984. In October 1984 the FDC set up their own office at Stalbridge Chambers, 435-443 Little Collins Street Melbourne. From 1982 - 1988 this building became an extraordinary creative hub for contemporary design, where hairdressers, filmmakers, artists, architects, solicitors and fashion designers all worked in close proximity to each other.

In November of 1984 this new 'advocate for the underground fashion world' held its first major event at The Venue, Earls Court St Kilda. Titled Fashion '84 - Heroic Fashion, this inaugural event took place over three consecutive nights and consisted of over 40 designers, 120 models and nearly 300 outfits. It was presented to enthralled packed houses on a two-tier stage with a 60 foot catwalk.

"It was possibly the biggest and certainly one of the most exciting and stimulating fashion parades Australia has ever seen." (Robert Buckingham)

With their new office now secured, and the success of their first major fashion event under their belt, the FDC was now established and recognised as a serious organization that supported young fashion designers, artists, craft workers and designers from other disciplines such as fine art, music, architecture, dance, communication and industrial design. From that point on the FDC were an unstoppable force, creating regular multi-disciplinary events incorporating catwalk parades, exhibitions and smaller fashion events at nightclubs, town halls, art galleries, theatres, and other notable venues around town.

Needless to say that the FDC events attracted a lot of mainstream and alternative media attention. From 1983 - 1985 Crowd magazine focused on design and culture connected with FDC activities, and in 1985 fashion magazine Tension ran an 8 page full-page photo feature of Fashion '84. Other Australian fashion magazines such as Fashion in Australia, Ragtimes, Collections, Virgin Press, Temper and Stiletto also covered FDC events or had a strong influence on the Melbourne underground fashion movement, while international fashion magazines Face and i-D informed local designers about new fashion trends. A regular FDC newsletter that documented group activities and published opportunities for members was also created and distributed.

As demand for labels soon became high, many designers worked and sold their clothing and accessories from their apartments or studios. And while some of the more successful designers had already established their own boutiques, many designers were unsuccessful in getting their DIY fashion from the catwalk to the street. So by the end of 1985 the old fashion conundrum of "It looks fantastic but would you wear it?" prompted the FDC to consider opening a retail shop, where many of their members would have a professional outlet to sell their wares. However it was to take an additional 3 years and some bureaucratic red tape before the FDC shop was to become a reality.

|

High Risk Dressing (FDC) - Robyn Healy.pdf Size : 6523.907 Kb Type : pdf |

|

High Risk Dressing Exhibition 2018 - RMIT.pdf Size : 7187.21 Kb Type : pdf |

In the meantime the FDC was growing exponentially in both member size and event magnitude. In April 1988 the FDC attracted major sponsorship from coffee giant Nescafé to the tune of $40,610, and held Nescafé Fashion '88 - Rabble Rowsers. Each designer was paid $400 as a base rate which enabled them to participate in the show and have five models. The show involved the transportation of 60 models, forty designers, four hundred outfits, stage, set, PA and the lighting crew. A film of the parade was also made and funded by Nestlé. By the end of the year the FDC had relocated to a new studio office at 404/328 Flinders street, Melbourne.

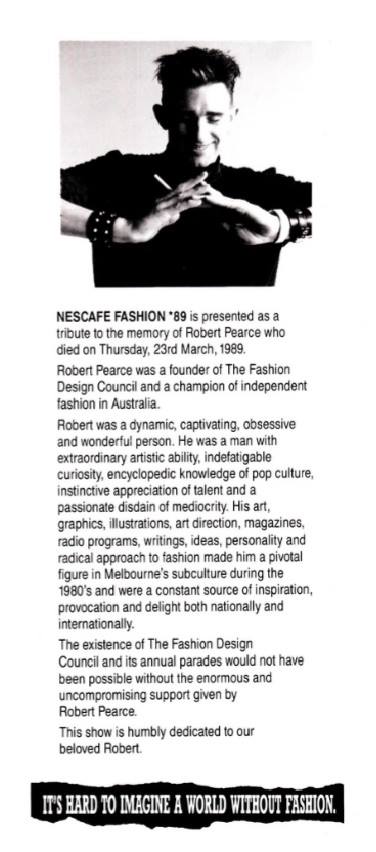

1989 was to be a turning point for the FDC. Sadly co-founder Robert Pearce died, but further funding from Nescafé saw the FDC expand into the Sydney market, presenting Nescafe Fashion '89 at both the Sydney entertainment Centre and the Melbourne Tennis Centre. Then in September, with a grant of $200,000 from the Victorian State Government, the FDC shop was finally realised and opened its doors at 234 Collins St, Melbourne.

A definitive one-stop shop for independent fashion, jewellery and accessory designers, the shop presented contemporary designs for fashion forward men and women between the ages of 18-25. Up to eighty young designers were shown in a gallery environment, and were actively promoted in parades, fashion press and Arts festivals. A booklet featuring eleven of the shop's top designers was also printed, and included: Abyss, Babble-On, Crypt, Dome, D'Zug, Ellen Ambe, Eileen Kirby, Ilona Aldred, Lea Femme, Peter Zygouras and Vivienne Savage.

However in order to satisfy the grant criteria, the FDC were required to create a separate entity called the Victorian Fashion Design Corporation (VFDC). A board of 12 advisors was also put into place to help run the shop and included merchant banker Richard Brezzo, accountant Andrew Avery, Myer fashion director Helen Rowe and Georges' accessories buyer Christine Dunbar, among several others. A shop manager was also required, with the chosen candidate being fashion designer Alasdair MacKinnon.

"I got involved finding sponsors for all sorts of stuff like paint, wall fittings and helping the designer/builders to put it all together. I was good at promoting the designers and running the education component - we had eager school groups through the store a couple of tines a week with students desperately wanting to know how they could become designers." (Alasdair MacKinnon)

But soon after the ink had dried on the lease the economy went into a nose dive and things became financially tough. Money became tight, the flow of foot traffic gradually decreased, and the FDC shop ultimately suffered. Although the shop held exhibitions and small in-house fashion parades, there was no money for the extensive marketing that was needed to drive traffic to the shop and keep it alive, and by the end of 1992 the shop had closed.

"We were successful at raising public awareness to the independent and largely unknown designers that had been bubbling up all around Australia over the previous 10 years, and providing a retail context that reflected that energy and design - and that was solely for the designers benefit. It was an amazing place that people who were outside of the scene or whom aspired to be a part of the scene found engaging and fascinating. We did an effective job of promoting fashion as a career and certainly inspired quite a few to have a crack." (Alasdair MacKinnon)

In its last few years of operation, the direction of the FDC changed. The institutionalisation of the underground or independent designer, coupled with the reliance on government funding and corporate sponsorship lead to tensions between creative directions and entrepreneurial success. In addition, the annual parade had become too expensive, with financial activities now centred around the shop.

The death of Robert Pearce also had a major impact on the other co-founders, and gradually the capacity to drive spontaneous, unconventional gatherings became diluted and less relevant. By 1992 the role of the FDC in communicating fashion practices was no longer potent.

In its almost decade of operation, the Fashion Design Council created 30+ fashion events at venues including the Crystal Ballroom, The Venue, St Kilda Town Hall, Inflations Nightclub, Hardware Club, Linden Gallery, Metro Nightclub, The Palais and the FDC shop.

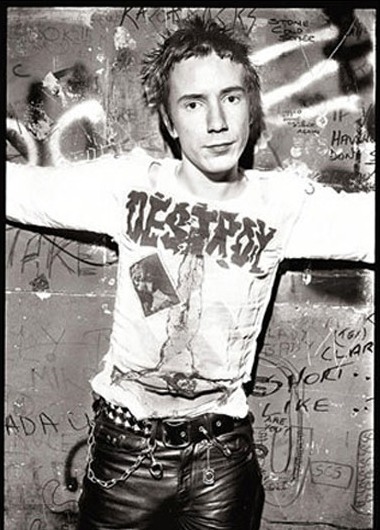

Johnny Rotten wearing Vivienne Westwood, 1977 Photo by Dennis Morris - Source: Widewalls

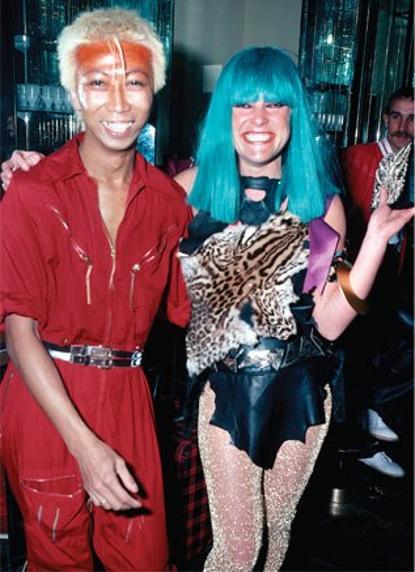

Leigh Bowery, 1988 - Photo by Nick Knight - Source: RoundSquare

The Fashion Design Council's multitude of members included designers such as: Jenny Bannister, Sara Thorn & Bruce Slorach, Gavin Brown, Fiona Scanlan, Morrisey & Edmiston, Peter Zygouras, Richard Neylon, Reva, Sark, Inars Lacis, Alasdair Duncan Mackinnon, Martin Grant, Desbina Collins, New Icons, Christopher Graf, Andoni, Glamour Pussy, Dome, Muse, D-Zug, Kara Baker, Susan Banks, Wayne Berkowitz, Jane Burke, Robyn Clewer, Anna Craig, Tamasine Dale, Kate Durham, Bern Emmerichs, Ahsley Franklin, Rosa Gateano, Bernie Goegan, Neville Kerr, Catherine Haywood, Sledge, Mitzi Skyring, Claudia and Pepa Mejia, Mandy Murphy, Stella O'Malley, Damian Macarthur Robinson, Paul Zgoda, Sue Lucas, Arnola Ephraums, Kathy McKinnon, Babble-On, Ken Thompson, Dinosaur Designs, Kara Baker, Harry Papa-Louis, Vivienne Savage, Eileen Kirby, BANKU$$I, Stephen Galoway, Peter Bainbridge, Peter Jago, Bettina Liano, Rebecca Emms, Dilemma, and many more...

- Main Image - Party Architecture program, 1983 - Source: Crusader Hillis and Rowland Thomson

- Background Image - Jenny Bannister leather design, 1976 and Ben Taylor hair c.1980 - Sources: Expired and Ben Taylor

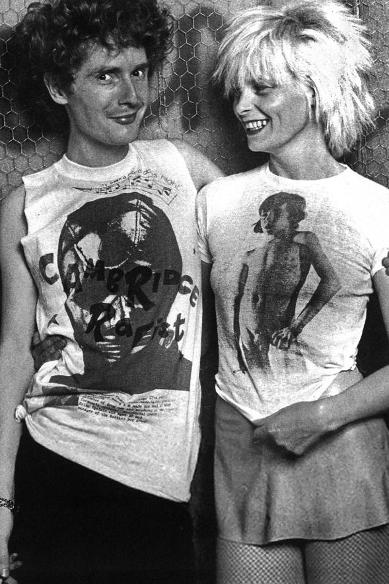

- Malcolm McLaren & Vivienne Westwood, 1976 - Source: Anothermag

- Johnny Rotten wearing Vivienne Westwood, 1977 - Photo by Dennis Morris - Source: Widewalls

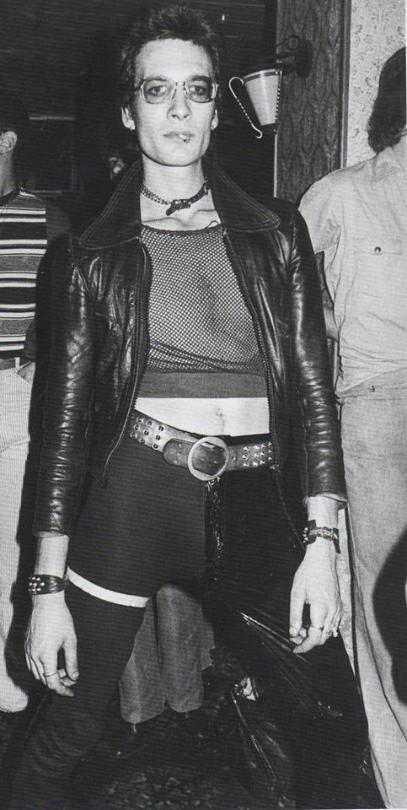

- Bohdan X, 1979 - Photo by Tanya McIntyre - Source: Timothy Hughes

- Clarence Chai & Jenny Bannister, 1981 - Photo by Rennie Ellis © Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

- Deborah Thomas, early 1980s - Source: Required

- Deborah Thomas and Pussy, early - mid 1980s - Source: Required

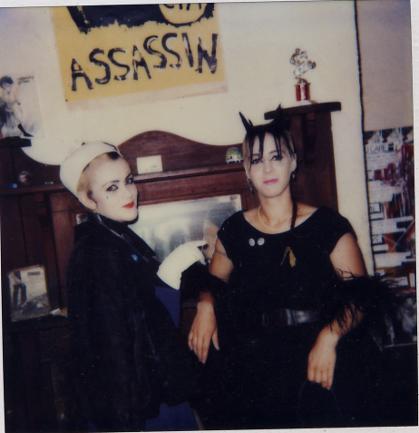

- Kate Buck & Wendy Gauwitz, 1979 - Source: Kate Buck

- Eccentric Clothing promo shot, 1980 - Source: Kate Buck

- Hair designs by Ben Taylor, c.1980 - Source: Ben Taylor

- Wattie, The Exploited, 1981 - Source: Expired

- Cherry Ripe, 1982 - Source: Cherry Ripe

- Hardcore house crew at a market, c.1982 - Source: Smeer

- Denise and Gillian, c.1983 - Source: Gillian Farrow

- Leigh Bowery, c. 1985 - Source: Pinterest

- Leigh Bowery, 1985 - Photo by Nick Knight - Source: Dazed

- Leigh Bowery, 1988 - Photo by Nick Knight for i-D - Source: RoundSquare

- Party Architecture article, 1982 - Source: The Age

- Cowprint

dress by Sara Thorn & Bruce Slorach, 1983 - Modeled by Alannah Hill

at Party Architecture, Photo by Polly Borland, Seaview Ballroom

- ABYSS Studio business card - Source: Sara Thorn

- FDC founders Robert Pearce, Kate Durham & Robert Buckingham, c.1984 - Photo by Ashley Evans - Source: Robert O'Farrell

- Fashion Design Council promotional images, 1984 - 1990 - Source: Duncan Mac, RMIT Design Archives

- FDC fashion parade images, 1984 - 1985 - Source: Duncan Mac

- Duncan Mac & friend @ Michaels Corner Store, 1984 - Source: Duncan Mac

- Bernie, 1987 - Photo by Rennie Ellis © Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

- FDC Video Party invitation postcard - everyone involved in Fashion '87 - Source: Kara Baker Archive

- Tribute to Robert Pearce, 1989 - Source: RMIT Design Archives

- FDC shop 1989-1992 - Photo by Penny Jagelio - Source: Alasdair MacKinnon and RMIT Design Archives

- Gates, Merryn (2011). Making it Up as We Went, Art Monthly Australia, Issue 242

- Gates, Merryn. Into the Abyss: designers Sara Thorn and Bruce Slorach and their journey from

Melbourne’s post-punk milieu to street labels Stussy and Mambo and beyond, Australian National University School of Art - Healy, Robyn (2002). Taboo or Not Taboo, the fashions of Leigh Bowery, Art Journal 42, NGV Publications

- Healy, Robyn (2012). High Risk Dressing by the Collective known as the Fashion Design Council, Chapter 9, pp.141 - 163 - Published as part of Edquist, Harriet & Vaughan, Laurene (2012). The design collective : an approach to practice. Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle

- High Risk Dressing / Critical Fashion, exhibition catalogue - Source: RMIT Design Hub Gallery

- Jennings, Sonia (2000). Chronology of Events for the Fashion Design Council, Monash University

- Party Architecture program, 1983 - Source: Crusader Hillis and Rowland Thomson

- Art and its Double: Fashion

- Precocious style: the Fashion Design Council, 1983–93

- The Design Council that changed Australian Fashion

- The Eternal Legacy and Influence of the Fashion Design Council

- Jenny Bannister Collection - Chai Parade, 1979 - Source: Jo Lane Vimeo

- The Legend of Leigh Bowery (1) - Source: Youtube

- FDC on Countdown 1984 - Source: Youtube and Countdown Memories

- FDC Special, Revolt into Style 1, 1985 - Source: Youtube and Countdown Memories

- FDC Special, Revolt into Style 2, 1985 - Source: Youtube and Countdown Memories

- Dick Hebdige - Source: Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London; New York: Routledge, 1991. and Subcultures - Love to Know

- Lisa Dethridge - Source: San Miguel, Dolores (2011). The Ballroom: the Melbourne punk and post-punk scene: a tell all memoir, Melbourne Books, p.8

- Jenny Bannister - Source: Vice

- Dolores San Miguel on Deborah Thomas - Source: San Miguel, Dolores (2011). The Ballroom: the Melbourne punk and post-punk scene: a tell all memoir, Melbourne Books, p.48

- Deborah Thomas - Source: Deborah Thomas

- Kate Buck - Source: Personal interview

- Ben Taylor - Source: Personal interview

- Smeer - Source: Personal interview

- Cherry Ripe - Source: Personal interview

- Robyn Healy - Source: Healy, Robyn (2002). Taboo or Not Taboo, the fashions of Leigh Bowery, Art Journal 42, NGV Publications

- Julie Purvis & Jillian Burt, 1983 - Source: Party Architecture program

- Sara Thorn - Source: Personal interview

- FDC Blurb - Source: RMIT Design Archives

- The Politics of Fashion, FDC - Source: RMIT Design Archives

- Robert Buckingham - Source: Jennings, Sonia (2000). Chronology of Events for the Fashion Design Council, Monash University

- Alasdair MacKinnon - Source: Personal interview

- http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=10726

- http://www.theage.com.au/news/Fashion/Staying-afloat/2005/03/11/1110417683899.html

- https://www.anothermag.com/fashion-beauty/3216/malcolm-mclaren-the-definitive-punk-visionary

- https://www.amazon.com/Destroy-Photographic-Archive-Pistols-1977/dp/1871592747

- http://punkflyer.com/seditionariesshop.html

- https://fashion-history.lovetoknow.com/fashion-history-eras/subcultures

- https://paulmcbride.me/2016/11/02/essay-the-punk-movement-in-the-realms-of-subculture-fashion-and-style/

- https://garnetbarnet.wordpress.com/tag/sex-pistols/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deborah_Thomas

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:British_hardcore_punk_groups

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hardcore_punk_in_the_United_Kingdom

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_hardcore_punk_bands

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hardcore_punk

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leigh_Bowery

- https://agnautacouture.com/2014/11/16/leigh-bowery-inspired-designers-photographers-a-painter-part-two/

- https://collection.maas.museum/object/155656

- http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/punk/images

- https://fashionphantasmagoria.wordpress.com/2014/08/24/australian-avant-garde-fashion/

- http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/exhibition/mix-tape-1980s/

- https://designhub.rmit.edu.au/exhibitions-programs/high-risk-dressing-critical-fashion/

- Kara Baker Archive - https://www.flickr.com/photos/sirensarchive/

- http://glossysheen.blogspot.com.au/2011/02/australian-young-designers-melburnian.html

- https://issuu.com/rmitdesignarchives/docs/rda_journal_8.1_web

- Kate Durham - https://www.katedurham.com/our-story